-

产品中心

-

解决方案

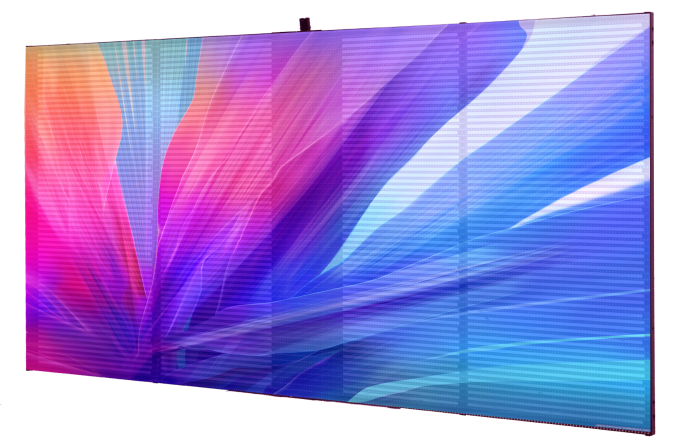

千赢体育倾心打造的高分可视化显控平台广泛应用于公安、军队、交警、消防、人防、城市应急等行业的指挥中心,集合各业务系统数据信息综合显示,数据、图形、图像、视频等信息联动切换,及各种高分辨率地理图像信息实时、全屏显示等功能,真正助力各指挥中心场景实现指挥扁平化、联动一体化、过程可视化的高效运作。

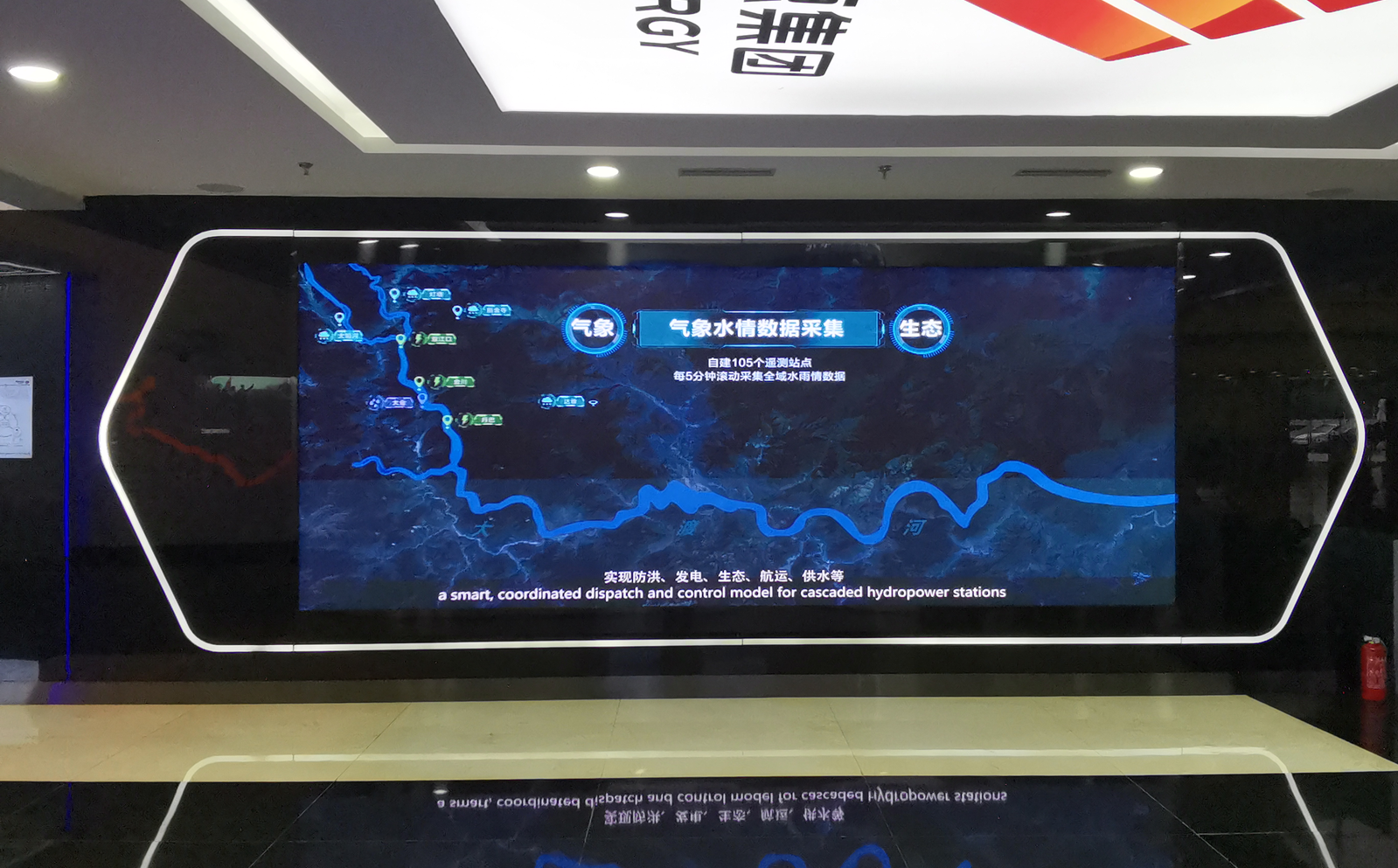

千赢体育高分可视化显控平台广泛应用于智慧城市、智慧交通、智慧能源、智慧安防、智慧网络、智慧园区、智慧党建等行业数据中心可视化建设中,提供各类业务数据汇聚、整合分析、动态监控、阈值预警、可视操作的超高清显示控制,为数据中心提供实时、直观、准确的智能显示平台。

千赢体育全媒体广电演播室解决方案以高清LED显示屏作为内容呈现载体,集合了虚实结合、虚拟植入、大屏包装、在线包装、融媒体接入、流媒体推送、数据可视化等为一体,在营造节目气氛、烘托气势、信息呈现多元化、加强现场主持连线、观众互动方面取得质的飞越,极大地增强了信息交互性和选择性,给观众以强烈的视觉震撼效果,为节目表现形式带来全新的革命。

千赢XR应用解决方案集成高清LED显示大屏、摄影机追踪系统及强大图形处理引擎,将动作捕捉、AR、VR、5G等技术应用深度融合,使得人物或产品等真实物体沉浸于虚拟世界而无需绿幕及后期制作即可完成虚拟制作。凭借优秀的载体和专业的解决方案设计能力,千赢XR应用解决方案可应用于企业产品发布活动、远程教学、虚拟影棚拍摄、电视演播、音乐现场、电竞赛场等场景沉浸式展示,为观众提供别开生面的创意数字体验。

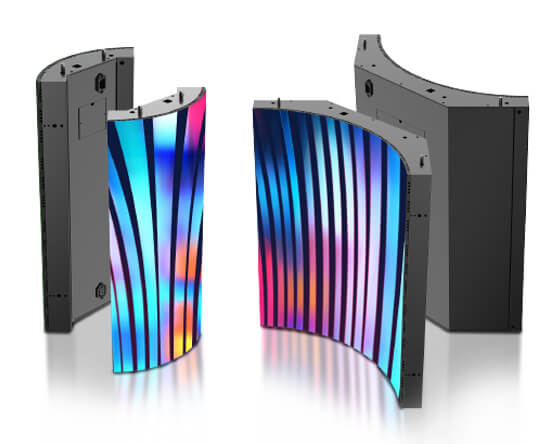

千赢体育为户内外传播场景,提供大屏+裸眼3D视频内容的一站式专业定制方案。凭借多年LED显示技术沉淀,突破性首创无缝曲面专利显示技术,革新传播载体;组建专业视频团队,推出专属片源定制服务,完美呈现震撼3D画面,提高大屏传播有效性,成就“黄金广告位”。

千赢体育“THE WOW”裸眼3D方案可广泛应用于产品发布会、企业展览展示、博物馆、科技馆、教育、主题娱乐等场景应用。无需佩戴特定设备、无需复杂的舞台设计,7屏7面的“W”3D造型即可一键解锁精美绝伦、酷炫震撼的多维光影力量。

千赢体育“汇议+”智能会议整体解决方案广泛应用于专业会议场景。借助LED显示屏卓越的显示效果,结合会前、会中、会后流程特点设计开发,具备简单、高效、完整、易操作、智能化等优点,主要应用于政府、事业单位和集团企业等用户群体各种中大型会议室、报告厅,多功能厅等,真正实现高效、便捷、智能会议。

千赢体育数字传媒解决方案广泛应用于交通枢纽户外广告、楼体商业创意广告、体育赛事户外广告、零售店广告等,为客户提供了广告播放、营造气氛、信息传递、品牌宣传、互动体验等一系列宣传手段,从而更有效地吸引消费者的关注,并助力品牌文化的推广传播。

的士屏可在移动中显示广告、新闻、气象等信息,与传统的广告发布媒体相比,具有流动性强、发布面广、信息传达率高、不受时间及空间限制的特点,现已成为广告信息传播的新型媒体,可为运营商带来收益,是一种极具投资价值的系统产品。出租车车顶LED显示解决方案,是千赢体育依托强大的生产制造基础、前沿的技术创新能力及丰富的广告显示屏经验,针对传统出租车车载信息显示屏的痛点再改造再升级,对产品线的再扩充再完善,也是对方案应用场景又一次丰富。

- 应用案例

- 服务支持

- 新闻资讯

-

关于我们

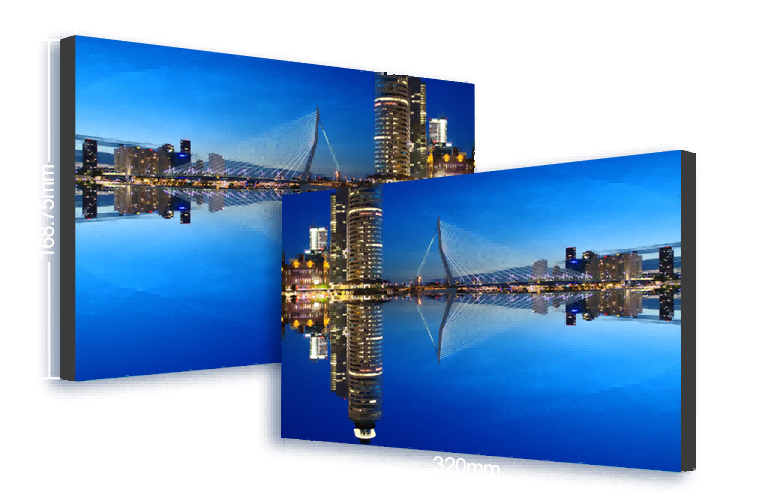

千赢体育成立于2003年,2011年成功在深圳交易所创业板上市,股票代码300269,是国内领先的LED显示屏供应商,为国内外客户提供中高端LED显示设备及显控系统的研发、制造、工程安装和售后服务等整体解决方案。目前已发展成一个员工超1300人,拥有已授权国家专利400余项的国家级高新技术企业。公司先后获得安全生产许可证、钢结构施工资质、系统集成资质、建筑机电安装工程专业承包叁级、电子与智能化工程专业承包贰级,并通过国军标质量管理体系认证。

千赢体育深耕数字显示设备市场,凭借丰富的LED显示行业经验与技术、管理团队,已获得“深圳市知名品牌”、“广东省守合同重信用企业”、“中国LED行业年度影响力企业”等多项荣誉。

千赢体育以“阳光、奋斗、创新、感恩”的新文化理念为人才培养和发展打造良好的组织氛围。以实现“511战略”展开的业务调整与组织变革将极大地拓宽人才发展的空间和激励人才潜能的开发。

千赢体育惠州科技园成立于2009年,建筑面积近8万平方米,每天近1000 ㎡ LED显示屏设计产能居世界前列。园区拥有国内先进的自动化专业生产流水线,已经形成产品规格齐全、质量优良、交期迅速的制造优势,以优质品质领跑全球LED显示市场。

-

联系我们

千赢体育服务网络遍布全国20多个省、市、自治区,并成立行业事业部分别针对军事、人防、广电教育、国企央企、能源五大行业特性,提供定制化个性化服务,纵观全球,千赢体育在美国、德国、莫斯科、巴西、印度、迪拜等全球12个国家设立营销服务中心,并配备百余人的工程销售服务团队提供本地化服务,为客户提供专业LED显示系统应用解决方案。

千赢体育服务网络遍布全国20多个省、市、自治区,并成立行业事业部分别针对军事、人防、广电教育、国企央企、能源、渠道六大行业特性,提供定制化个性化服务,纵观全球,千赢体育在美国、德国、俄罗斯、巴西、印度、阿联酋等全球12个国家设立营销服务中心,并配备百余人的工程销售服务团队提供本地化服务,为客户提供专业LED显示系统应用解决方案。

2020年,千赢体育正式推出“向阳计划”,全面开启全国经销商拓展活动。“阳”,指代太阳,广大经销商合作伙伴犹如我们的太阳,而联电团队如同向日葵般紧密团结在一起向阳而生,守望太阳。